By Katherine Wolkoff, Travel + Leisure

In college, I studied American history. The Vietnam War is an integral part of that story, and it has always been a prominent event in my mind.

My parents got married in 1969, and while my dad didn’t fight in Vietnam, both he and my mom protested the conflict here in the States. When I was about 10 years old, in 1986, they took me on a six-week trip to Asia. It felt like we traveled everywhere — China, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaysia — but we didn’t go to Vietnam because it hadn’t opened up yet.

I’ve traveled a lot at this point in my life, and I’ve long felt a specific pull toward that missing experience. Through reading history and literature, I’d developed these ideas of what the North and the South were like, how they were distinct because of the way they’d been governed and developed. In many ways, the most tangible connection they shared was the North-South Railway, a 1,072-mile network built by the French during colonial rule that stretched from Hanoi to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). Rebuilding this infrastructure, which was originally constructed in 1936 but bombed and nearly decimated during the next 40 years of war, became a signature project for the postwar government, which managed to repair thousands of tunnels, bridges, and stations in less than two years.

In college, I studied American history. The Vietnam War is an integral part of that story, and it has always been a prominent event in my mind.

My parents got married in 1969, and while my dad didn’t fight in Vietnam, both he and my mom protested the conflict here in the States. When I was about 10 years old, in 1986, they took me on a six-week trip to Asia. It felt like we traveled everywhere — China, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaysia — but we didn’t go to Vietnam because it hadn’t opened up yet.

I’ve traveled a lot at this point in my life, and I’ve long felt a specific pull toward that missing experience. Through reading history and literature, I’d developed these ideas of what the North and the South were like, how they were distinct because of the way they’d been governed and developed. In many ways, the most tangible connection they shared was the North-South Railway, a 1,072-mile network built by the French during colonial rule that stretched from Hanoi to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). Rebuilding this infrastructure, which was originally constructed in 1936 but bombed and nearly decimated during the next 40 years of war, became a signature project for the postwar government, which managed to repair thousands of tunnels, bridges, and stations in less than two years.

|

“The mix of war remnants

and temples in Ho Chi Minh City, where I shot this picture of the

People’s Committee Building and the ‘Uncle Ho’ statue, makes it feel

very multifaceted,” Wolkoff says.

|

The railway’s reopening in 1976 symbolized the country’s coming back together — hence its nickname, the Reunification Express. The more I researched, the more I felt like the train was the most cohesive, immersive way to experience a wide swath of the country. I convinced my high school friend Tess to tag along as my “assistant.” We’d traveled by rail through Europe together in our twenties, but hadn’t had the chance to spend much time together since.

Our seven-day trip started with 48 hours in Hanoi, with the Sofitel Legend Metropole as our base. The capital city felt chaotic but vibrant — dripping hot during the day, but cool and clear in the early morning. A guide took us through the wild markets, and we ate papaya salad and pork-and-crab dumplings that the vendors turned in the fryer with beautiful long chopsticks. And while I’d eaten Vietnamese food before, I discovered that pho — basically the country’s version of chicken-noodle soup — makes a perfect breakfast. It sounds counterintuitive to eat something hot when it’s scorching outside, but it actually cools down your body. During the day, we caught taxis and tuk-tuks and had to fight our way through streets packed with motorbikes. We’d stop at shops selling fabrics in a riot of colors, and the markets were even livelier at night when the lights came on and more people came out.

|

From left: “I woke early

to explore Hanoi’s food stalls in the morning. The fruit—in this case,

rambutans and mangoes—was amazing.”; “When I photograph people, I

usually snap first, then deal with the repercussions. But most people

there, including the monk in Hoi An, were fine with it.”

|

|

“When I photograph

people, I usually snap first, then deal with the repercussions. But most

people there, including this father-daughter pair in Hanoi, were fine

with it.”

|

From there, we took a four-hour bus ride to Ha Long Bay to spend a day and night cruising on one of the old-fashioned Chinese-style junks that ply these waters. The midday heat could get oppressive, but in the morning and evening hours, there were these sublime moments when the temperature cooled and everything felt peaceful. I snapped pictures during a hiking excursion on one of the islands, and some kayakers drew my eye, but most captivating were the fishermen who live and work on their boats, leaving them only to sell their catch at market. The area in general sparked my imagination partially because the scale of the topography was so amazing and much of it is inaccessible, but more because as I sat on the roof watching the scenery pass by, I could imagine what it had been like during the war.

|

A traditional Chinese-style junk cruises through Ha Long Bay, in northeastern Vietnam.

|

After Ha Long Bay, we headed back to Hanoi to board our first train, a 17-hour overnight stretch that took us along the coast south to Da Nang. I learned quickly that, as with photography, taking the train in Vietnam requires flexibility, but you start to find humor in situations that don’t go as expected. I’d read the train schedule wrong, which meant we had showed up with about three minutes to spare before the train departed. For the first hour, Tess and I hunkered down by the water cooler while the conductors figured out which car we were supposed to be in. The train cars were all nice and modern, but the sleeping arrangements and seating types varied, as did the air-conditioning.

|

Wolkoff woke early to

capture the sunrise on the ride from Hanoi to Da Nang, which she found

to be the prettiest part of the trip.

|

On every assignment, it seems like I have to learn a new way of photographing. In this case, I woke up at 4:30 a.m. to shoot at sunrise and spent a good portion of the morning trying to convince the conductors to unlock the windows so I could get better shots unobstructed by the glass. The train went through rice fields with Catholic churches in the distance, and then along the coast, which is tropical with the green sea and white angel’s trumpet flowers growing everywhere. At some point, one of the conductors even grabbed my camera and took portraits of me.

|

Rice paddies in the province of Ha Tinh, with the Parish Church of Thinh Lac on the horizon.

|

We pulled into Da Nang in the afternoon and hopped in a taxi to Hoi An, a picturesque port town where I could see Vietnamese history punctuated by Chinese, French, and Japanese influences. At first, it felt touristy, but that feeling subsided at night, when we took a boat out onto the Thu Bon River and bobbed past lanterns in the water. The real magic happened the next morning, when I woke to walk around 5:30 a.m. I loved being up before everyone else arrived. It gave me the chance to appreciate the textures and colors — the magenta of the flowers and the orange and yellow of the lanterns in this speckled light.

Another 17-hour train ride — decidedly less bucolic than the first — took us from Da Nang to Ho Chi Minh City, which is where the complicated layers and history of the country came into the starkest relief for me. Vietnam is one of five remaining Communist countries, and this is very much a city in change, being modernized and developed over and over. At the War Remnants Museum, there was an exhibition of combat images taken by members of the Magnum photographers’ collective, and though I’d seen many of them before, revisiting them after having just traveled through the land where it all took place stirred intense emotions.

|

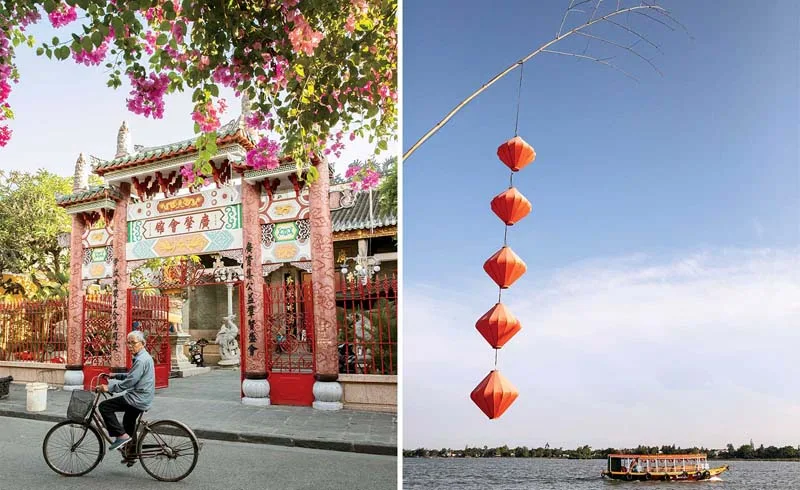

From left: “The Cantonese

Assembly Hall in Hoi An was filled with dragons and altars covered in

flowers, incense, and fruit.”; “Lanterns and flags popped up everywhere

in Hoi An. Both add nice texture to images.”

|

The funny thing is, not many people take the train through the country and see the sights these days, because it’s very slow and the delays can be frustrating. At one point, when one of our departures was pushed five hours back, I got fed up and wanted to fly between cities instead. But that’s when Tess reminded me: taking our problems in stride would give us a new perspective — which was the whole point of going to Vietnam in the first place.

![[feature]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgZv3ZLR6BuddAqBtEf49bM4Sf90BHifv77-2pln-XNEyeVydGud8bSAi2GhCjEijcJE3-v_hBhL_Llml6OgJnVA3e7G4Knk0nf7Citq4nWnUXJmE7iNd9q_tAchXZ2pGSaLJQFYvd9En5r/s1600-rw/1.jpg)

See more at: Travel + Leisure